Environmental Governance and Policy

Air pollution

Thirty and Still Dirty: Why Do Delhi’s Roads Remain So Polluted?

20 February 2025

A lot of road dust seen above the street. Source: Pexels

Delhi is frequently listed as one of the most polluted cities in the world. It is also riddled with potholed roads, suffers from severe traffic congestion, and is home to a massive vehicular population. This is especially hard to comprehend since road dust and vehicular emissions (hereafter referred together as road-based emissions) have been the focus of anti-air pollution action for about three decades.

A 1997 white paper on Delhi’s air pollution identified the transport sector as the chief culprit, estimating that it accounted for 72 percent of ambient air pollution. Since then, Delhi’s tortuous tryst with its transportation sector has seen many twists and turns, such as the conversion of buses and autos to CNG, the poorly executed bus rapid transit system, the sporadically implemented odd-even road rationing program, the introduction of the Delhi metro, the recent leap to Bharat Stage (BS) VI fuel and vehicle emission norms, incentives for the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), and the introduction of schemes for vehicle scrappage.

At the national level, around 67 percent of funds under the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) have been spent on road dust, and 14 percent has been spent on vehicular pollution. As of November 2024, Delhi had utilised just 32 percent of the funds allocated under the NCAP, amounting to Rs 13.56 crores. As per a submission made to the National Green Tribunal1, these funds were meant primarily for activities targeting road-based emissions such as purchasing mechanical sweepers, pothole repair machines, end-to-end paving, and creating green buffers along roads. Yet, road-based emissions continue to remain a significant contributor to ambient air pollution.

How bad are road-based emissions?

Within the transport sector, much of the focus has rightly been on exhaust or tailpipe emissions, as fine particulate matter (PM2.5) – particularly those generated by the combustion of fossil fuels – poses severe risks to human health due to their ability to penetrate deep into the respiratory and circulatory systems, causing long-term adverse effects.

Several source apportionment studies have investigated the contribution of road-based emissions to overall ambient air pollution concentration in Delhi over the years. Guttikunda et al. (2023) summarised 11 different studies between 1990 and 2022 and concluded that vehicle exhaust from petrol, diesel, and gas combustion accounted for 10 to 30 percent of annual average PM2.5 concentrations, making it one of the four largest sectoral sources contributing to Delhi’s poor air. Another of the four major sources is dust from roads and construction, further highlighting the role of road-based emissions.

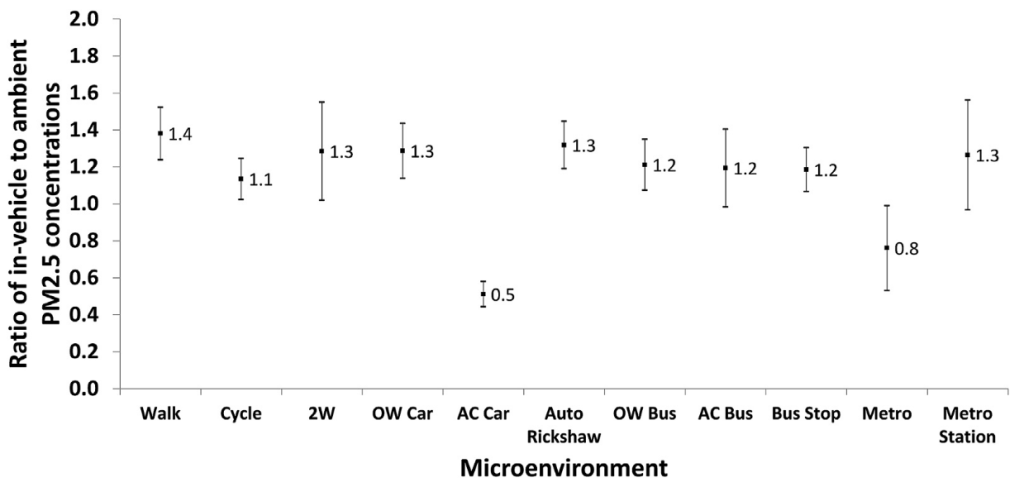

The health impact of road-based emissions is even worse than is suggested by source apportionment studies. This is because the exposure to these sources is much higher while commuting in the city. As Figure 1 shows, compared to ambient PM2.5 concentrations, commuters across most modes of travel in Delhi are exposed to 10 to 40 percent higher levels of PM2.5. This makes road-based emissions even more harmful when taken together with the long commute times prevalent in the city.

A tale of historical logjams and emergent challenges

The seemingly intractable nature of road-based emissions is due to several different factors:

1. Delhi roads are poorly constructed and maintained.

Road dust is composed of a complex mixture of materials, including soil erosion, vehicular wear and tear, degraded road materials, construction debris, degraded plastics, biomass residues, and industrial waste. It constitutes a significant portion of the coarser PM10 and a smaller but more toxic fraction of PM2.5. Vehicles grind and wear down road surfaces, releasing particles, while wind and vehicle turbulence resuspend settled particles. Seasonal factors, such as the low humidity during winters reduce moisture that otherwise settles dust, leading to higher suspension rates. Further, ongoing construction activities, poorly maintained roads, potholes, unregulated waste dumping, and insufficient street cleaning amplify road dust generation.

Over the last few years, numerous promises to repair and redesign roads have been made (Figure 2). However, these commitments have yet to result in any significant change. Delhi’s roads continue to face persistent issues, including unpaved roads left by service agencies, numerous potholes, cracks, and craters caused by poor maintenance, uneven surfaces, and inadequate drainage leading to waterlogging. Delays in repair approvals and substandard resurfacing quality further exacerbate these problems. In 2022, 1,637 accidents and 320 fatalities were caused due to poor-quality roads in the city.

Among these issues, waterlogging accelerates the deterioration of bituminous pavement layers, and many roads lack proper slopes to drain rainwater. Bituminous blacktop cannot withstand standing water effectively as its adhesion to underlying layers is weak, and this leads to surface patches peeling off and forming new potholes. Moreover, multiple layers of blacktop carpeting raise the height of the road surface thereby adversely affecting drainage, which allows rainwater to infiltrate sewer lines through manholes in depressions caused by uneven resurfacing. Furthermore, the city’s drainage system managed by multiple agencies (mainly the Municipal Corporation of Delhi and the Public Works Department) is designed to handle a limited amount of rain, leading to clogged drains that exacerbate waterlogging.

2. The Delhi Metro is not enough to shift the city away from private vehicle ownership.

Prior to 2022-23, Delhi had over 1.4 crore registered vehicles. Now, that number has reduced to about 80 lakhs, due to the deregistration of old and polluting vehicles. Since 2001, the personal vehicle segment has seen high growth, with 92.6 percent of all registered vehicles belonging to this category in 2023. Taxis and e-rickshaws have grown very sharply, while autorickshaws have plateaued and buses have declined (Table 1).

| 2001 | 2023 | Percentage Change | |

| Population (in lakhs) | 138 | 213 | 54% |

| Total Registered Vehicles | 34,56,579 | 79,45,596 | 130% |

| Cars & Jeeps | 9,20,723 | 20,71,115 | 125% |

| Motorcycles & Scooters | 22,30,534 | 52,94,900 | 137% |

| Auto Rickshaws | 86,985 | 93,654 | 8% |

| Taxies | 18,362 | 83,278 | 354% |

| Buses2 | 41,483 | 17,232 | -58% |

| Goods Vehicles | 1,58,492 | 2,65,739 | 68% |

| Ambulances | – | 1,172 | – |

| E-Rickshaws | – | 1,18,506 | – |

| Deregistered Vehicles | – | 62,59,2143 | – |

The preference for personal vehicle ownership in Delhi is clear. Apart from being seen as a means to boost social prestige, personal vehicles are almost unavoidable in a city where public transport and last-mile connectivity are very unreliable. For example, when considering intracity bus transport – comprising Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) and licensed private bus services – the number of buses has grown by a mere 16 percent over 22 years. After nearly 3 decades and several government initiatives, Delhi has yet to meet the target of 10,000 buses set by the Supreme Court in 1998. In fact, on a per capita basis, there were 25 percent fewer buses in 2023 than in 2001 (Table 2). Given that only 22 percent of Delhi’s population moves in private cars, car ownership will continue to increase and the recent de-registration drive is unlikely to have a lasting effect.

| 2001 | 2023 | Percentage Change | |

| DTC buses | 3524 | 4346 | 23% |

| Cluster/Blueline buses | 2685 | 2841 | 6% |

| Total buses | 6209 | 7187 | 16% |

| Buses per lakh population4 | 45 | 34 | -25% |

The Delhi metro is the largest metro rail network in the country, but it suffers from lower-than-expected ridership and is also unaffordable for many. Metro systems are very expensive to construct. They are great for travel over longer distances but are typically far more cumbersome to use for short-distance travel. Metro stations are almost always not accessible without relying on some other form of paratransit, particularly due to the poor condition of footpaths in the city. In the absence of reliable non-motorised transport options such as walking or cycling, as well as a weak bus service, e-rickshaws have become the city’s primary para transit mode, offering cheap last-mile connectivity. The relatively high transaction cost of getting to and from a metro station has made it a less attractive option for those who can use private vehicles or taxis.

3. Not just more vehicles, but also larger and heavier vehicles

(a) The increase of freight

Road transport, predominantly facilitated by trucks, carries most of India’s goods, accounting for 70 percent of the current domestic freight demand. With the continued growth in road freight travel, the truck population is expected to rise significantly at the national level, from 4 million in 2022 to nearly 17 million by 2050. According to a 2020 estimate, approximately 1.69 lakh freight vehicles enter Delhi daily, and as per another estimate from 2018, trucks were the most polluting vehicle category in the city.

A pervasive issue is truck overloading. Overloaded trucks exert excessive pressure on road surfaces, accelerating their deterioration and shortening the life of roads. This not only increases maintenance costs but also creates significant safety risks for all road users. Research indicates that pavement damage increases exponentially with axle load, such that if the axle load doubles, the damage to the road surface increases by a factor of 8. Major factors contributing to overloaded vehicles include economic pressure on truck operators, lack of enforcement and monitoring, and inadequate infrastructure such as weigh stations.

Several steps have been taken over the years to address the overloading of freight. A Supreme Court judgment from 2018 mandates that any truck exceeding 10 percent of its allowed weight limit will face a fine of ₹20,000 for the first tonne of excess weight and ₹2,000 for each additional tonne. Additionally, the judgment instructed state governments to establish weighing stations to monitor the weight of commercial vehicles. Last year, the Delhi government proposed to authorise traffic police to take action against overloaded goods vehicles, a power so far held by the transport department. The proposal seeks to reduce congestion and prevent polluting vehicles from entering the national capital region.

(b) The proliferation of SUVs

Sports Utility Vehicles or SUVs are now the dominant variant of cars in India5. Over 50 percent of all cars sold in 2024 were SUVs. While the exact number of SUVs in Delhi is difficult to determine, their popularity is a safe assumption to make. One key reason for the form factor’s success is its superior performance on uneven, potholed, and crowded Indian roads. These vehicles allow for a higher vantage, a smoother ride, and a perceived dominating road presence.

But it is these very virtues that make SUVs a problem. First, SUVs emit more air pollutants and carbon dioxide relative to other cars. They are heavier than sedans and hatchbacks and their tall profiles also make them less aerodynamic. This makes them burn more fuel per kilometre, which directly translates into increased air pollutant emissions. SUVs are such large emitters of CO2 worldwide that when placed alongside national emissions they rank 5th on the list. Second, SUVs are heavier, so they produce more non-exhaust emissions such as those produced from the road, tyre, and brake wear. Taken together, it forms a vicious cycle of increasing pollution and road wear caused by those who chose to circumvent those conditions by adopting SUVs in the first place. Third, in a city with an acute shortage of road and parking spaces, they take up an inequitably large share.

4. Vehicles are emitting more than they should

Over the years, vehicular emissions norms have been strengthened, with the latest BS VI standard being a significant improvement over the older BS IV. Further, older vehicles in Delhi must adhere to strict deregistration rules, allowing them to be used for only up to 10 (for diesel vehicles) to 15 (for petrol vehicles) years. Unfortunately, the rise of heavier personal vehicles – also known as autobesity – has the potential to reduce and even counteract such environmentally beneficial measures. This is because the recent shift to SUVs implies that despite the introduction of newer vehicles, they may not necessarily be as clean as intended. This does not mean that BS VI SUVs are dirtier than cars running on BS IV or older standards. In theory, it means that replacing a lighter but more polluting older car with a heavier but less polluting newer car is not likely to reduce emissions as much as replacing it with a lighter, or better yet, an electric car.

Ensuring that vehicles continue to run clean on roads has proven to be challenging as well. Vehicles operating under the latest BS VI emissions standards are polluting more than expected, with real-world emissions found to be as much as 14 times higher than the standard-approved limits. One key reason for this is that the only in-use emissions test for vehicles in India – known as the Pollution Under Control or PUC certification – does not even check for key pollutants such as PM2.5 or oxides of nitrogen.

5. The future must have both more EVs and fewer vehicles overall

Given this context, EVs have been rightfully identified as the key to significantly reducing transport emissions in Delhi. The benefits of eliminating tailpipe emissions cannot be understated, and the potential benefits to ambient air quality in the region due to a complete shift to EVs will be immense.

Yet, much like the Delhi metro or the CNG transition before it, it is important to remember that EVs are not the panacea. With renewable energy sources taking up more of a share in electricity generation, the displaced emissions from charging EVs are likely to reduce in the future but concerns about the ability of renewables to replace fossil energy as a base load source and thermal power plants delaying the installation of pollution control technologies will have to be addressed. EVs also produce non-exhaust emissions via road, tyre, and brake wear. The impacts of these emissions are still being understood, but emerging evidence suggests that they are very harmful.

In India, while a shift to EVs must be wholeheartedly embraced, it is also important to extract as much environmental gain as possible from this shift. Unfortunately, autobesity has found its way to the EV space as well – most new electric car launches are now SUVs. EV SUVs are doubly inefficient, because a larger vehicle needs a larger battery, adding to the mass and the energy inefficiency of the vehicle, and producing larger batteries adds to both the economic and environmental cost of the vehicle, as batteries are still quite expensive and are manufactured in ways that adversely impact the environment.

Crucially, EVs are designed to be direct substitutes for existing vehicles. Issues such as congestion, land use for parking and roads, and automobility-dependent urban sprawl will not be addressed by EVs. Electrification will do nothing to combat issues born out of car culture, such as the absence of good quality footpaths and dedicated cycling lanes. Thus, the electrification of vehicles must be integrated within a larger rethink of transportation design in the city.

The way forward: towards a more people-centric Delhi

So, what are some ways to reduce road-based air pollution in Delhi? They are largely no different than what needs to be done to improve the state of transportation in the city.

Irony has defined Delhi’s fight against its transport woes. Over the last 30 years, even as the city has tried multiple elaborate and expensive ways to fix these issues, it has become more car-centric and polluting than ever before. What is needed is a painful switch away from the philosophy of building a city that revolves around easing the flow of vehicular traffic. It is a design choice that is doomed to fail, as theoretically postulated by the Jevons paradox6 and as witnessed in practice by all of us. Building more roads always results in more vehicles.

City planners and policymakers must instead focus on building a city that is pedestrian and cyclist friendly. The metro rail network and city bus routes already provide the necessary connective tissue needed to stitch together longer distance travel in the city, and so it is the shorter distance commutes that cannot be effectively met by these modes that need to be addressed. Footpaths of sufficient width need to be provided on every road. Cycling lanes should be added wherever possible.

Building the necessary infrastructure is just the first step. Delhi has failed to provide a reliable and comfortable service experience to users even after numerous attempts. The maintenance of footpaths and cycling lanes requires significant improvement, and doing so can lead to substantial gains in local air quality. Pedestrian infrastructure and roads should also be treated with equal importance in an integrated manner, to prevent roads being incessantly widened at the cost of footpaths. Developing pedestrian and cycling infrastructure can also improve economic opportunities, promote safety and encourage the city to get healthier.

The next step will be to address the high levels of exposure to air pollution experienced by pedestrians and cyclists. The most direct solution is to reduce the absolute number of vehicles on the road. Disincentivising the purchase and use of personal vehicles (via congestion taxes, for example) will seem far less coercive if non-motorised and transit alternatives of a similar quality and reliability are made available simultaneously.

The quality of Delhi’s bus services will have to be improved. The introduction of car-free zones, such as the one in the high-footfall area of Chandni Chowk, is an important step in the right direction. Better emissions norms, effective enforcement of said norms and eventually, a complete shift to EVs will also achieve a significant reduction in emissions load.

Finally, improving the condition of existing roads will ensure their optimal utilisation. Ensuring effective drainage, robust pavements, and effective traffic management can improve the flow of traffic without widening roads.

These solutions are not new. They have been tried and tested in numerous contexts around the globe. These experiences all point to the same conclusion – that Delhi has to make these simple yet painful decisions in order to build a city that serves its people and not its vehicles.

Footnotes

- Submission made by the Delhi Government dated 19 February, 2024 under the Original Application No. 687/2023. Copy available with authors. ↩︎

- Includes all registered buses in the city, including but not limited to Delhi Transport Corporation and cluster buses, as shown in Table 2. ↩︎

- These are the vehicles de-registered by the Delhi Government as of 2023, following the ban on old diesel and petrol vehicles. As per the Delhi Statistical Handbook 2023, of the 62 lakh de-registered vehicles only 1.4 lakh vehicles were scrapped and a further 6.2 lakh vehicles were given a No Objection Certificate for operating in other states. The fate of the remaining 55 lakh vehicles is unclear. ↩︎

- Data sources for population numbers are the same as in Table 1. ↩︎

- The definition of what an SUV is is not exactly clear. Many Indian SUVs can also be labelled as cross-overs between a hatchback and an SUV. However, it is safe to assume that almost all SUVs in India are larger and heavier than hatchbacks and most sedans. ↩︎

- Jevons paradox states that as the use of a resource becomes more efficient, the demand for that resource increases as well, leading to an increase in overall resource use. In Delhi, this can be seen in the form of improvements in roads leading to an increase in vehicle ownership, which in turn leads to the further crowding of roads. The paradox was first described in the book The Coal Question. ↩︎